Blue Pearl 2

Culturing Abalone Half Pearls

Blue pearl 2, the story of New Zealand Eyris Pearl™

by Pam Hutchins FGAA

Wide Bay Valuation Services, Bundaberg

(Used with Permission)

Thanks, Pam, for suggesting that I add your informative paper to KariPearls.com.

Part 2

Part 1 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5

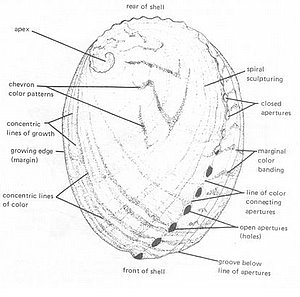

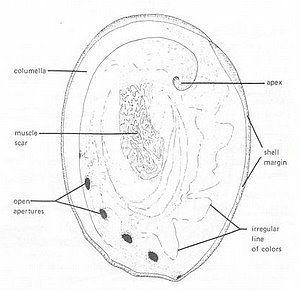

Fig. 2. Gross anatomical features of the abalone shell, RHS - external view, RHS internal view. Adapted from Howarth (1978) Blue Pearl 2 The univalve shell of the abalone has an oval shape, but is more pointed towards the head of the mollusc. The external surface of the shell (Fig. 2A) is characterized by the presence of a series of respiratory apertures that close towards the rear of the shell, and a spiral shaped apex that is located to the rear of the shell. Concentric growth rings are readily visible towards the front of the shell. Internally (Fig. 2B) the shell is lined with nacre, of variable iridescence, which is patterned by the scar of the muscle attachment to the inside of the shell, and the internal manifestation of the whorl of the shell’s apex. A flattened columella extends along the rim of the shell from the rear of the shell to the region where open respiratory apertures are readily visible.

How it reproduces

When spawning, eggs and sperm are released from the gonads of female and male abalone through a series of respiratory pores (apertures or holes) in the shell through which the abalone draws oxygenated sea water to its gill. This is known as broadcast spawning. One 37 mm abalone may spawn 10,000 eggs or more at a time, while 21 cm abalone may spawn 11 million or more. Spawning is usually controlled by factors such as water temperature or the length of the day. Additionally, the presence of eggs and sperm in the water may stimulate other abalone to spawn, thus increasing the chances of fertilization.

Fertilized eggs hatch as a microscopic, free living larva that drift with the currents for about a week. Then the larva settles to the bottom, shed their swimming ‘hairs’ (cila), and begins to develop into their shell-bearing adult form. If a suitable habitat is located, the abalone may grow to adulthood. However, the chance that an individual larva will survive to adulthood in the ‘wild’ is very low.

It is interesting to note that while the sexes of the abalone are quite separate, they can be identified as either males or females (based on the colour of their gonads) as soon as they are about 25 mm in size (when the gonads have begun to develop).

Age and growth

Determining the age of an individual abalone is difficult, for unlike the hard parts of some animals the abalone shell has no regular pattern of growth marks or bands suitable for assigning age. However, it has been estimated that aquarium-bred juvenile abalone grow at the rate of 2-3 cm or more per year for the first two years. Tagging studies have provided some estimates of the rate of growth of larger abalone in the wild. For example, red abalone (H. rufescens) are mature at 4-5 cm, after which growth begins to slow with age. Therefore, an 18 cm red abalone may be 7-10 years old, while one only 2 cm longer may be 15 years of age or older.

ABALONE HALF-PEARL CULTURE

Production of stock

Stock suitable for implantation are obtained both from the ‘wild’ and from spat culture.

Spat (very young abalone) are purchased either from privately owned or government controlled hatcheries, where they have been raised from fertilized ova in a series of special hatchery tanks. The smaller paua (those of 5 mm) size are kept in the special tubes so that they can attain a good size that will help their subsequent survival when replanted into the ‘wild’ (ocean waters).

(You are reading blue pearl 2)

Hatchery bred juveniles are returned to the ‘wild’ (their natural environment) in a process known as ‘reseeding’. Subsequent growth to maturity in these somewhat protected environments will give the juveniles a good chance of survival and growth in the ‘wild’, for their food will be plentiful and they are somewhat protected from their natural predators. These factors should ensure fast growth, and this helps to replenish levels of ‘wild’ stock in the waters around New Zealand.

Throughout their life in the ‘wild’, abalone have to contend with a variety of natural predators—with eggs and larvae being eaten by other filter-feeding animals; juvenile abalone that are nocturnal (active at night) often becoming natural prey for crabs, lobsters, octopuses, starfish, the cabezon fish, the bat ray, and of course sea otters; while mature abalone are attacked by a range of parasites that include shell boring worms, boring barnacles polycheaete worms, and various species of polydora worms. To survive in the ‘wild’ abalone need to hide under water, firmly attached to rocks and in crevices within masses of rock. In addition, an algal bloom can suffocate the abalone and destroy a whole population both in the ‘wild’ and in the waters of a pearl culture farm.

An annual quota of ‘wild’ abalone is allowed to be harvested from the ocean waters surrounding New Zealand, near the rocky shoreline and on the rocky shallows of the continental shelf. For Eyris Blue pearls™ this annual quota is currently 23 tonnes.

THE CULTURE OPERATION

Location of farms

Fig. 4. Location of Eyris Blue Pearls™

pearl culturing operations.

Blue Pearl 2 |

Eyris Blue Pearls™ operate five pearl culture farms at geographically isolated locations (Fig. 4) in the cool waters that surround New Zealand. The company’s first farm was established in 1989 at Whangamore Inlet on the Chatham Islands. These remote islands lie some 800 km to the east of Christchurch. The second and third farms were established on Banks Peninsula to the south of Christchurch (Fig. 5). Presently these farms act as holding areas for new stock before they are moved further out to sea for grow-out following implantation.

Fig. 5. Pristine waters of Akaroa Bay on the

Banks Peninsula, site of one of Eyris Blue

Pearls’™ pearl culturing operations.

Blue Pearl 2 |

The fourth farm, which is located at Tory Channel in the Marlborough Sounds on the north of New Zealand’s South Island, is now in full production. The latest farm is located in Wellington Harbour on the south of the North Island. Presently, this farm is being used to cultivate seaweed to feed the abalone.

Selection of stock

Fig. 6. Characteristic iridescent

nacre of the ‘wild’ H. iris.

Blue Pearl 2 |

It is considered that ‘wild’ abalone that grow naturally, or are derived from reseeded hatchery-bred spat have good genetic diversity, and are ideal for producing cultured pearls. This fact is highlighted by the strong and vibrant iridescent colours that can be observed (Fig. 6) on the nacre that lines the shells of ‘wild’ abalone. Abalone chosen for collection as ‘mother’ abalone must neither have any evidence of marine borers in their shell, nor display any evidence of disease or deformity. Usually this is the case of only one mollusc in twenty that is inspected in the ‘wild’ and deemed to be suitable for use as a producer of a cultured pearl. When harvesting the license holder’s annual quota of abalone from the ‘wild’, divers do not use air tanks. Instead, these divers use free diving technology and must have very good lung capacity. It is thought that this conservative collection philosophy gives the abalone a more than reasonable chance of not being fished out.

The legal size of the ‘wild’ abalone that can be fished for stock is a shell length of 125-135 mm. This size equates to an age of 4-5 years. It is believed that this size restriction gives more young ‘wild’ abalone a chance to attain adulthood and become the future ‘mothers’ for pearl cultivation.

You are reading Blue Pearl 2

Return to Part 1 after Blue Pearl 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Learn more about abalone pearls

After reading Blue Pearl 2 maybe you'd like to show us some natural abalone pearls you've found.

Have you found an abalone pearl? Add a page about it here. We'd love to hear about it and see a photo.

I hope you enjoyed blue pearl 2

Enjoy this page? Please pay it forward. Here's how...

Would you prefer to share this page with others by linking to it?

- Click on the HTML link code below.

- Copy and paste it, adding a note of your own, into your blog, a Web page, forums, a blog comment, your Facebook account, or anywhere that someone would find this page valuable.